In people who experience acute pain due to a stroke, trauma or cancer the most potent pharmaceutical painkillers eventually lose their effectiveness. Doctors frequently must prescribe larger and higher doses for patients to get the same pain-relieving benefit.

It is yet unclear why people develop this tolerance to opioids. The latest research, performed by Martemyanov and colleagues, reveals a crucial function for the gene PTCHD1, which modifies the amount of cholesterol in a cell’s membrane. The study raises the prospect that cholesterol in the cell membrane may also alter how people react to other drugs, opening new avenues for the development of pain medications.

Advertisement

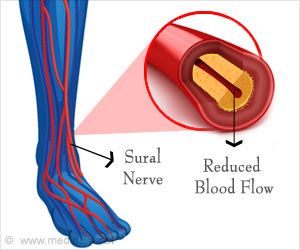

On the surface of cells, hundreds of receptors serve as landing pads for drugs and biological substances. Mu opioid receptors specifically capture morphine or similar chemical molecules, like a catcher at home plate in baseball. When they do, cellular mechanisms in charge of reducing pain, slowing breathing and even altering digestion are triggered. GPCR, which stands for G-protein coupled receptors, is a category of landing sites. A GPCR is involved in about one-third of all drugs, which is why researchers are interested in them.

The researchers were shocked to discover a gene that affects cell membrane cholesterol to develop opioid tolerance. Brock Grill, PhD, formerly of Scripps Research and currently of Seattle Children’s Research Institute and the University of Washington Medical School, was Martemyanov’s co-author on the paper.

“There are more than 800 known G-protein coupled receptors, and regulation of cholesterol by genes in this family could be important to understanding many of them. A significant step forward in the search for a new class of painkillers less likely to lead to overdose is understanding how cholesterol may influence tolerance,” said Martemyanov, who chairs the UF Scripps Department of Neuroscience.

The researchers made the decision to carry out an ‘unbiased’ genetic screen using a particular kind of microscopic worm known as C. elegans in their attempt to comprehend opiate tolerance. Without preconceived notions of which genes might be involved, unbiased genomic screens enable the biology of the organism to show what is occurring. For this goal, scientists frequently employ less complex animal models, such as worms.

To make C. elegans worms sensitive to painkillers, they first modified the genomes of the worm to add the human mu-opioid receptor. The genetically altered worms first became paralyzed when given fentanyl and morphine treatments. However, this impact subsided over time as the worms built up a tolerance.

Then, random genetic modifications that silenced different genes were applied to the genetically changed worms. Those who ceased displaying tolerance were chosen for additional testing to determine what set them apart. A membrane protein-encoding gene stood out among the others. PTCHD1 was the closest mammalian equivalent of this gene.

Role of PTCHD1 in Developing Opioid Tolerance

The scientists discovered that little was known about the gene’s role in cell function in humans, even though it was linked to neuropsychiatric disorders. To see whether the effect occurred in mammals similarly, the researchers then studied mice created to lack PTCHD1. Mice lacking the gene not only failed to build a tolerance to opioids after repeated exposure, but they also had fewer withdrawal symptoms once treatment ended.

PTCHD1 is a member of a gene family linked to controlling cholesterol build-up in cell membranes. Because of this, the researchers investigated whether cholesterol played a role in tolerance. In fact, scientists discovered that excessive PTCHD1 expression drastically decreased the cholesterol level of the cell membranes.

Could increasing cholesterol in the cell membrane be a tactic for lessening opiate tolerance?

Researchers turned to well-known drugs to provide an answer to that query. Simvastatin, a regularly given medication for decreasing cholesterol that also raises the high-density lipoprotein, or HDL, a component of cholesterol, was discovered by the researchers after a series of trials. Simvastatin-treated mice displayed no tolerance to repeated opioid challenges.

The researchers hypothesize that cholesterol influences the cell receptors directly by binding to them or by indirectly regulating cellular processes downstream. There is still more to do. Researchers hypothesize that more genes in this family may play a role in controlling cell receptors like the mu-opioid receptor.

Source: Medindia