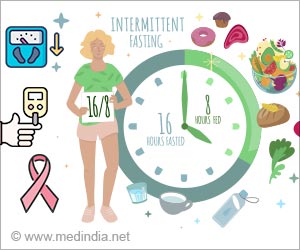

Stanislawski collaborated with CU Department of Medicine associate professor Vicki Catenacci, MD, who led a behavioral weight loss intervention study comparing the effects of two popular weight loss regimens – intermittent fasting and the more traditional approach of daily caloric restriction.

Stanislawski examined the effects of the intervention on the gut microbiota of the participants and found that both approaches have a positive impact on helping diversify the microbiome.

Diverse Approaches to Dietary Intervention: Fasting vs. Continuous Caloric Restriction

In one group, participants were instructed to fast three non-consecutive days per week. On fasting days, the participants were to eat about 25% of what they normally eat, and on non-fast days they could eat whatever they wanted. In the other group, participants were instructed to reduce calories every day by the same amount, about 30% of their weight maintenance needs. Participants were also given behavioral support during the intervention and advised about ways to improve their overall diet quality as well as encouraged to increase their physical activity levels.

Advertisement

“Dr. Catenacci and her team were aiming to understand intermittent fasting because it’s become really popular, but some clinicians are hesitant to recommend it for weight loss,” Stanislawski says. “This could give people who are trying to lose weight more options. As you might imagine, being able to eat whatever you want on a specific day, such as for a party or social engagement, is really helpful.”

In a pilot study focused on the first three months of the one-year intervention study, researchers noted several changes in the microbiome in both groups of participants.

“There are various measures of the microbiome that we tend to think about,” Stanislawski explains. “One of them is called alpha diversity, and these measures represent the diversity of the different types of microbes in an environment. While not always true, a more diverse and robust microbiome is often associated with better health and leanness. This is probably because if you have a more diverse set of microbes in your gut, then you have more microbes that can respond to a diverse set of health impacts.”

“We looked at different measures of alpha diversity that take into account various features of diversity,” she says. “They all increased in the first three months of this intervention, which is great. When we looked at differences between the two intervention groups, there weren’t really any differences in terms of alpha diversity.”

The results from the study suggest that, in terms of the microbiome’s diversity, both dietary weight loss strategies are equally successful. Similarly, they saw changes in the overall taxonomic structure of the microbiome composition across all participants in both intervention groups.

“This means that you can choose a dietary weight loss strategy that works for you, and either way your microbiome will likely shift and increase diversity,” Stanislawski says.

CU researchers Emily Hill, PhD, RDN, in the Department of Pediatrics, and Iain Konigsberg, PhD, in the DBMI, worked with Stanislawski and Sarah Borengasser, PhD, and several other researchers across the CU Anschutz Medical Campus, on a new study using the same behavioral weight loss intervention data.

The researchers examined the relationships between the gut microbiome and blood DNA methylation. DNA methylation, Konigsberg explains, is the dynamic process of addition and subtraction of methyl groups, which are single carbons to cytosines, the C base of DNA.

The Role of DNA Methylation in Gene Regulation

“It’s one of the multiple epigenetic mechanisms that regulate our genes without directly altering our DNA sequences,” he says. “DNA methylation is a dynamic process, and it impacts compaction of our DNA and accessibility by regulatory machinery. The idea is that, very broadly speaking, increased methylation at gene regulatory regions generally represses expression of those genes.”

“One of the biggest appeals of epigenetic mechanisms is that they are a means through which the environment can act to alter our genes and our health,” he continues.

For example, smoking tends to have a big effect on DNA methylation.

“You have certain genes whose activity put you at a greater risk of some type of disease, but if you live a healthy lifestyle, they aren’t activated,” Konigsberg says. “But if you’re a smoker, they start going haywire.”

In the behavioral weight loss intervention study, associations between the gut microbiome and DNA methylation were observed among participants.

“Our results reinforce this idea that we may see a lot of changes in microbes that are associated with diet and obesity during weight loss,” Konigsberg says. “We also see abundance of microbes associated with DNA methylation levels in genes that we know are involved in relevant processes in the body, such as metabolism.”

Both studies from the DBMI researchers open a window into how diet impacts not just the microbiome and its diversity, but also the rest of the body.

“We are able to show these downstream effects in the body that are associated with the gut microbiome – and may even be mediated through the actions of these microbes,” Konigsberg says.

Reference :

- The Microbiome, Epigenome, and Diet in Adults with Obesity during Behavioral Weight Loss – (https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/15/16/3588)

Source: Eurekalert