Leqembi has also been named as one of The Best Inventions of 2023 in the Medical Care category in TIME’s annual list featuring “200 extraordinary innovations changing lives.”

In July, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a version of Leqembi that is administered twice monthly through the veins, which is a method known as intravenous infusion.

Advertisement

But the new study shows promise for a subcutaneous version of the drug, which would be an injection under the skin. This method can help patients or caregivers administer the Leqembi at home, freeing them from the need to travel to a hospital every two weeks.

Japan’s Eisai and its US-based partner Biogen in a statement said they plan to apply for US approval of subcutaneous Leqembi by the end of March.

Promising Path to Slowing Alzheimer’s Progression

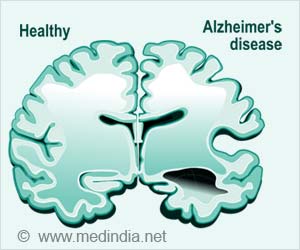

Alzheimer’s disease is an irreversible, progressive brain disorder that slowly destroys memory and thinking skills and eventually, the ability to carry out simple tasks.

While the specific causes of Alzheimer’s are not fully known, it is characterized by changes in the brain — including the formation of amyloid beta plaques and neurofibrillary, or tau, tangles — that result in the loss of neurons and their connections.

Presenting the study, at the 16th annual Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) conference held in Boston, the companies said the new study tested subcutaneous doses of Leqembi amyloid – also known as plaque – that builds up in the brain.

The findings revealed that a set of two injections administered once weekly produced similar results after six months to twice-monthly intravenous infusions in terms of safety, the concentration of the drug in the blood and its ability to clear plaques in the brain, Eisai said.

The injectable form of Leqembi removed 14 percent more plaque than the approved intravenous formulation. Blood concentration levels of the drug were 11 percent higher with subcutaneous Leqembi than the other version.

However, the newer form still showed side effects known as amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA).

The removal of plaques from the brain can be associated with brain swelling and bleeding – also known as ARIA-E and ARIA-H – which can be severe or even deadly in rare cases.

Almost 17 percent of patients who got weekly injections had ARIA-E, compared with 13 percent who got the drug via intravenous infusion. And 22 percent of those taking the shots had ARIA-H, versus 17 percent who received the other form.

Source: IANS