, especially in times of crisis, such as the period that followed the COVID-19 outbreak. And policymakers could use these results to better devise surveillance/monitoring systems to contain, minimize, and even anticipate surges in domestic violence.

Koksal teamed up with former PhD colleague Ebru Sanliturk (Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research) and consulted former Bocconi scholar Valentina Rotondi (SUPSI and University of Oxford), who was working on a similar topic with former Bocconi student Luca Maria Pesando (McGill University). They joined forces and analyzed the relations between Google searches for nine domestic violence-related keywords on one hand, and calls to the Italian domestic violence helpline 1522 and to the emergency number 112 in Lombardy on the other.

Advertisement

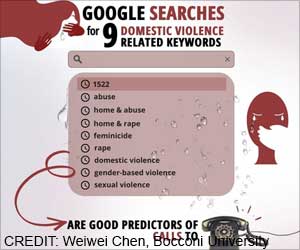

The selected keywords were: 1522 (the domestic violence helpline number in Italy), abuse (abuso), home & abuse (casa & abuso), home & rape (casa & stupro), feminicide (femminicidio), rape (stupro), domestic violence (violenza domestica), gender-based violence (violenza di genere), and sexual violence (violenza sessuale).

The idea underlying the study is that the Internet and Google in particular may offer a medium to anonymously voice concerns about abusive partners and collect relevant information. Calls to the helpline (1522) measure the potential risk of experiencing domestic violence, while calls to the emergency number measure actual violence.

The frequency of queries for keywords 1522, feminicide, domestic violence, and gender-based violence are consistently positively and significantly correlated with helpline calls across the whole investigated time period (2013-2020), with a time lag between search and call of around one week.

Their predictive power increases after the COVID-19 outbreak, when traditional help mechanisms became harder to reach.

Online searches help predict actual violence only in crisis scenarios. Only after the COVID-19 outbreak, in fact, there is a positive and significant correlation between searches for four keywords (1522, abuse, domestic violence and sexual violence) and calls to the emergency number.

Finally, the authors observed a worrying socio-economic divide. “Forecasts proved more reliable among high socioeconomic status population,” Koksal said, “because they are better than other socioeconomic strata at googling effectively in this context. It may be the case that individuals with lower socioeconomic status use dialect or less targeted keywords, which could prevent them from reaching accurate online resources for seeking help.”

The authors advise policymakers to track domestic violence-related searches and to accordingly intensify their support activities, both reinforcing services where and when searches become more frequent and raising awareness through the media. “They could also intervene in favor of disadvantaged people,” Koksal concluded, “by promoting internet literacy and, in the short run, convincing Google to show domestic violence support services among the top results, as it has done in the US.”

Source: Eurekalert